*Published in Think Space MONEY. Zagreb: DAZ, Think Space Programme, 2014.

By Patricio De Stefani

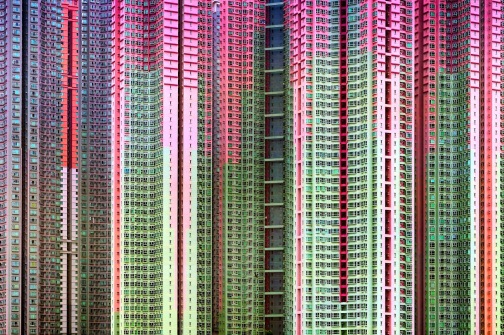

Architecture of Density #39, Michael Wolf.

Abstract

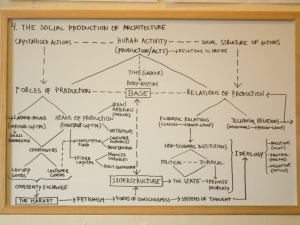

Does money really ‘rule’ the world? If money is just the form of appearance of exchange-value, does not a more substantial reality lie behind it? What if money is just a means to realise something far more complex, namely, capital? If this is the case, what sort of architecture has the capitalist mode of production engendered and how? If the production of value is what characterises simple commodity production in pre-capitalist societies, the production of surplus-value defines the capitalist mode of production. How is this surplus produced? Where does profit come from? Only by understanding till what extent capital is embedded in the production of architecture a way to challenge that relationship can be thought about. This process could not have taken place without the integration of architecture, and space in its entirety, into the circuits of capital. Therefore, if capital is a process in which the value contained in commodities continuously changes its form in order to expand itself, then, as soon as architecture steps into this circuit as means of production (a factory or office building, for instance) it turns itself into capital – as constant capital, or more specifically, fixed capital.

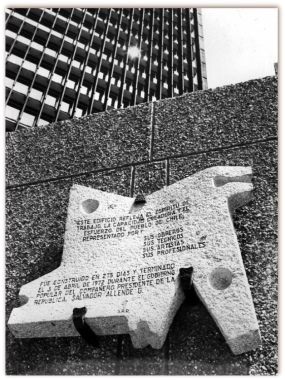

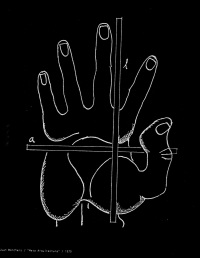

Abstract space was born out of the violence and ‘creative destruction’ of primitive accumulation and the establishment of the modern state. Essential to this was also the increasing role of urbanisation in the expansion of markets, eventually reaching the whole globe. Built upon the historical process of abstraction of labour and space, psychologists, art historians and architectural theorists developed the modern concept of space towards the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This concept presented ‘space’ as a neutral and autonomous void/volume divorced from the social and political practices which produce it. Indeed, the reduction of space to this apolitical, visual-aesthetic, or purely empirical state is no mere ideology, but fulfils a precise practical function: to ensure the reproduction of social relations of production. This is not achieved without major problems though. Contradictions internal to the development of capitalism (notably between capital and labour) are increased at the spatial level as a simultaneous tendency towards an absolute homogenisation and fragmentation of space. Space and architecture become real abstractions (like money or capital), apparently autonomous and rational objects which aspire to homogenise whatever stands on the way of the forces of accumulation (the state and the world market), paradoxically, by means of fragmenting and subdividing space according to their requirements. If space/architecture can serve political and economic purposes by reinforcing the reproduction of production/property relations, could it serve as a device to confront these relations?

Keywords: Value, Capital, Abstract Space, Abstract Architecture

We often hear ‘radical’ common wisdom complain about money as the ‘root of all evil’, or the conservative one as the ‘necessary evil’, but evil anyway. What those well-intentioned moral critiques usually forget is that money is just another commodity, but a very special commodity indeed. Just to name a few of its ‘special properties’: it measures the value of all other commodities at the same time it allows their trade or circulation. Does money really ‘rule’ the world? If we spend half of our live making it and the other half spending it, who could think it does not determine a huge part of it? But what is behind the mystery of money? Is money always capital? What is their relation to social space and architecture?

In what follows I intend a historical approach to the process of abstraction of space by which architecture was transformed to fit the requirements of capital accumulation in the emergence of bourgeois society. It will be argued that only by understanding till what extent capital is embedded in the production of architecture a way to challenge that relationship can be thought about. Continue reading